Anthropomorphism: An Academic look at Character Creation for business entities and assets.9/15/2015  Excerpt from: Chicago Booth Capital Ideas Magazine " Anthropomorphism—giving human characteristics to animals, objects, constellations, and other nonhuman things—is a natural and ancient human inclination. Eighteenth-century philosopher David Hume wrote about a “universal tendency among mankind to conceive all beings like themselves”—a tendency, he argued, that stems from an intellectual urge to understand a frightening and erratic existence. All over the world, and throughout time, people have fashioned gods after people—and some have envisioned god-favored heroes in the constellations. Sailors named storms and hurricanes, a tradition continued by meteorological organizations. We see faces in clouds and trees, and attribute to our pets motivations that we can’t prove. In the past few decades, thanks to advances in technology, we have created things that talk, sing, dance on screen, smile, frown, and exhibit nuanced human expressions. We think of products and brands as other people with fully formed personalities—as companions, friends, and relationship partners. When companies develop anthropomorphized characters, consumers pay attention. A video of geeky, dancing hamsters shilling for Kia has more than 8 million views on YouTube. But despite our apparent need to anthropomorphize objects, the issue was rarely studied from a business perspective until recently. Now researchers are beginning to understand the psychology of anthropomorphism, which can be a useful tool—not only for selling cars and other products, but in understanding how we interact with animals, computers, and entire ecosystems. Anthropomorphism could be used to help overcome fears about self-driving cars, or to persuade a sometimes-skeptical public to confront climate change. A sense of humanity, we are learning, is a powerful motivator. What makes us see humans everywhere? Hume implied that our anthropomorphism is uniform. Nicholas Epley, John Templeton Keller Professor of Behavioral Science at Chicago Booth, disagrees. He says that when it comes to assigning human qualities to things, there’s huge variability. We don’t even anthropomorphize the same object in all situations. Sometimes, he points out, we start a car and press the pedal. Other times, we may pet its dashboard and plead for it to start. “It changes over the course of a lifetime, in different situations, and across different cultures,” says Epley. Though it contradicts our higher logic, we still get sucked in: we know a talking peanut can’t exist, yet he’s an endearing and remarkably adept salesperson. We know that a computer that crashes right before a big presentation can’t be out to get us, but we curse at it anyway. It seems to be in our nature to humanize things despite our capacity to reason—or perhaps in part because of it. Read More

0 Comments

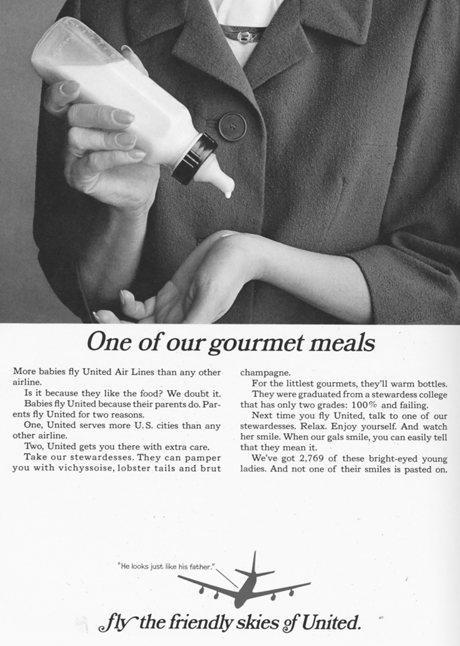

Packaging a brand with a sellable message to hide its ethos sounds archaic. Back then in the 60's it was cutting edge. In this case the ad agency might have permanently altered UA's core value and persona unintentionally. Brand authenticity was seldom an agency's first priority unless it contributed to short term revenue boost. Sure, culture can change but it takes leadership's vision and time. Selling the friendly skies

BY VICTORIA VANTOCH, AB’97 | UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MAGAZINE —JULY–AUG/13 American stewardesses and the making of an iconic advertising campaign. ECONOMICS & BUSINESS | EXCERPT During the Mad Men era, virtually every heavy-hitting advertising agency was based in New York City. But hundreds of miles away, the boutique Leo Burnett Agency on East Randolph Street was proving itself a formidable competitor. In 1963, the Leo Burnett Agency was invited to bid for one of the nation’s most coveted ad accounts: United Airlines. Leo Burnett, the acclaimed ad- man behind the small Chicago agency, corralled his top creative team. They poured themselves into brainstorming sessions—analyzing United’s image, strategizing the pitch, and waxing philosophical about the future of air travel. Later that year, a cadre of United executives in pinstriped suits convened in a smoky boardroom to hear the admen’s pitch. The Burnett team laid it out: United was the General Motors of air travel—“professional, official-looking” and “a little stuffy and cold—coldly efficient, with a production-line attitude.” Then came the real blow: the ad team called United “stodgy” and “dull.” William Patterson, United’s president since its beginnings in 1934, prided himself on the airline’s hard-won reputation for reliability, but he knew that United desperately needed to sell more seats... - Full Article Something I have been trying to emphasize with my partners and clients. However it's very hard to implement the change, not the technical nor the tactical part but the philosophy, strategic vision of the business and its core business model. Take McDonald for example, it did a great jobs in the recent years trying to portrait a healthier and greener image for itself. Unfortunately its core operation such as recipe and ingredients would not likely to change if the law is not broken or the negativity externality not exposed (We thank the whistle-blowers for keeping the pressure on). How can it be transparent and authentic if the message of being good is only a marketing pretext while the core strategy is still maximizing profits legally while not optimizing (health, as one of many) benefits for the customers? At the moment, it is much harder for a large corporation than a small startup to achieve genuine authenticity and transparency. “We are currently losing $25 million per day,” Postmaster General Patrick Donahoe warned earlier this month. Somebody save the poor Postman please! Take it private if necessary.

The bad management of USPS has trickled down to the end user level. Customers are more annoyed beyond rate increases and long lines. USPS has worsened the quality of their products and customer service as a response to their own failing/winning product and marketing strategy. I had a fun chat with a staff yesterday on Flat Rate Priority Mail. Besides raising the intl priority flat rate by ~20%, they also degraded the envelope with flimsier, easier to torn recycle stock; and you are NOT allowed to reinforced the edge with tape, or it'll be treated as “package”, when they are obliges to charge you much, much more. It was USPS' innovative idea to offer flat rate priority mail to customers: all you can put inside the envelope for up to 4 pounds for a flat rate. It seemed to work well for the postmaster and customers, for a while until recently... About a year ago my mom started dreading going to the post office to forward me my posts via intl flat rate priority mails. Every time she went the postal staffs started harassing her about the envelope being too heavy (usually around 2 pounds); until I nudged her to remind them about the 4-pound rule (their own rule), then they stopped. I was told that the employees were pressured to discourage customers from taking advantage of the offer to improve revenue.(???) Internet eliminated most of our needs on sending letters but increased our reliance on them (and other carriers) thanks to online shopping. E-commerce sales during the holidays increases by 16 -18% per year, 4 years in a row. Was USPS able to capture any of its spill-over benefit? There is something obviously not working with its management and business strategy. Let alone customer service (I haven't even touched on their pickup-note-instead-of-package delivery strategy). if they continue this route we might one day see this great American brand turns into another bygones. Please, somebody save this USPS. Article on Facebook Envy: The name “Facebook” finally makes sense to me, because it's really all about the “surface”, the superficial stuffs.

Most of us in our shared networks came from a generation of never to display our closet' skeletons nor our laundry in the open; and share only the happy events in life. Only those who are really closed to us have seen our worst... very few of our failures would be recorded on our timelines. No wonder we see only hot chick and rods, extravagant vaca and sappy family photos on FB. I never posted about my dad having a stroke last summer (more a blog material). I'm aware not to be a party pooper on FB, cause it's a happy place for us to flaunt and bond. Ranting about others, politicians, celebs is however acceptable and very appropriate cause we bond even easier when we share our hate against common nemesis. Those born in the 90's and after have a very different way of using FB. I love glancing their posts! They openly broadcast their success and failures, loves and hates... yet the consequence of doing that has relatively less impact since most of them are still dependents with very little to no life obligations. Personally I don't take FB too seriously. I like to entertain and be entertained by images or words. It's a GREAT way to connect with new and old friends currently living in different time zones. However I rely mostly on personal visits to connect/reconnect whenever possible. Fb after all is really just a surfacebook, but I did make a few great friends such as Jeffrey Jones and Kerrin Howard whom I met first on FB. |

Filip Yip:A designer, illustrator, repro-media consultant, brand strategist, new product developer, real estate investor, new venture builder, scuba diver, martial artist… and most importantly, husband and father, Filip holds a BFA from The Academy of Art University in San Francisco, and an MBA from The University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He is constantly seeking equilibrium between Form and Function; Purpose and Survival; He is equally comfortable with fuzzy feeling and fussy Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|